Popularized by the Chinese-born American geographer Yi-Fu Tuan in 1974, the term “topophilia” describes the affective bond between people and place or physical environment.1 Topophilia, Tuan wrote, “varies greatly in emotional range and intensity,” such as fleeting visual pleasure, a sensual connection that delights the senses, a fondness for that which we call home, and joy on account of well-being and vitality.2 Topophilia emphasizes our attachment to place and the symbolic meanings that underlie this attachment. It encompasses both the physical and psychological dimensions of our relationship with the environment we live in.

One powerful manifestation of topophilia is the connection between individuals and their homeland. More than just a physical location, homeland embodies a complex web of personal and collective identities, cultural values, and historical narratives. It frequently evokes a deeper set of attachments than those predicated purely on the visual. The bond between people and their native land is often forged through generations, shaped by shared experiences, traditions, and a sense of continuity.

One’s homeland can act as a source of inspiration, shaping an individual’s perception of themselves and the world around them. It provides a sense of rootedness, a place where one feels deeply connected, understood, and welcomed. The connection to homeland nurtures a profound sense of attachment, fostering a longing for the familiar and a desire to protect and preserve the essence of one’s cultural and geographical origins. It is a fundamental part of human existence, contributing to a sense of identity and shaping our relationship with the world. The following projects explore the connection between people and places. Each reflects a native ecology or landscape, conveys a distinct sense of one’s culture or homeland, and supports a deeper understanding of the multiple manifestations of biophilia.

A collaboration between Tohono O’odham artist Terrol Dew Johnson and the New York– and Tucson-based design studio Aranda\Lasch, the Desert Paper series embodies the rich material history of the vast Sonoran Desert (cats. 1–3). This unique ecosystem, abundant with biologically diverse resources, has been inhabited by Indigenous peoples for millennia and holds significant cultural and historical importance to the Tohono O’odham Nation.3 To create the paper baskets, Johnson gathers vegetation and other natural materials, including agave fiber, copper, creosote, jute, mesquite bark, volcanic rock, and wildflowers that are endemic to the Sonoran Desert from various locations around Tucson and Sells, Arizona. Johnson skillfully combines these various elements with a natural pulp paper, which is then carefully draped over bent screens to form expressive and irregularly shaped baskets. Each vessel in the series is a unique work of art, characterized by its distinct texture, color, and appearance.

Desert Paper celebrates the rugged, yet fragile, beauty of the Sonoran Desert, the very landscape from which it is created, while also honoring the profound human connections to this environment (fig. 1). For Johnson, utilizing these regional and culturally traditional materials is a way of reaffirming the Native identity, specifically that of the Tohono O’odham people, of these baskets, while forging a connection between these experimentally shaped vessels and the ongoing tradition of Native craft and knowledge-sharing.

The work of Santiago-based design collective gt2P (great things to People) often reflects the natural landscapes of Chile. Bordered by the majestic Andes Mountains in the east and the vast Pacific Ocean in the west, the country lays claim to the second largest and most active chain of volcanoes in the world. The Remolten N1: Revolution series pays homage to Chile’s volcanic landscapes and celebrates nature’s ability to create beauty through volcanic activity (cats. 26–28). With each eruption, magma emerges from the earth’s surface. Molten lava transforms the existing terrain and cools to form an entirely new landscape until the next eruption occurs. Within the confines of their studio, gt2P replicates this dynamic natural activity. The process begins with the harvesting of basaltic andesite, a lightweight and porous black rock, from Chile’s Osorno Volcano, located in the Andes Mountain range roughly 650 miles south of Santiago (fig. 2). A landmark of the Los Lagos region, the 8,700-foot-high snow-topped landform towers over Todo los Santos and the shores of Llanquihue Lake. While Osorno is one of the most active volcanoes of the southern Chilean Andes, it has not erupted since 1869. Osorno’s activity is dominantly effusive, with magma rising through its surface and flowing out as viscous lava.

After collecting the volcanic stone, gt2P grinds it into a powder, applies it by hand to the surface of stoneware structures, and then fires the objects in a kiln, treating the volcanic powder as a ceramic glaze. Through extensive experimentation, gt2P discovered that the melting points of certain volcanic rock perfectly coincide with the firing temperature of porcelain. This convergence enables the lava to melt as the ceramic hardens within a specific temperature range. By adjusting the firing process at various temperature curves, they control the resulting colors, resistance, and surface texture, yielding an array of unique objects such as planters, side tables, stools, mirrors, and chairs. Each piece showcases distinctive tactile characteristics, ranging from smooth to dripped and rough finishes (fig. 3).

Imbued with emotion and the spirit of the natural world, artist Alexandra Kehayoglou’s lush and tactile carpets depict the disappearing and decimated ecosystems of her native Argentina. Kehayoglou’s hand-tufted landscapes also draw attention to the beauty and importance of safeguarding her homeland’s fragile ecological resources. “If activism has the task of ringing the alarm, art and design can offer ways to connect us with something beyond. Something more spiritual,” Kehayoglou explains. “We must hold on to hope . . . hope offers a path forward.”4

Many of Kehayoglou’s carpets examine Argentina’s pastizales, or grasslands, a once vast and fertile plain that covered a significant expanse of the country, from the Atlantic Ocean to the Andes Mountains (fig. 4). Argentina’s grasslands biome has been severely transformed by human development, including the long-forgotten region buried beneath bustling Buenos Aires. Kehayoglou began portraying the pastizales as a way of recounting and acknowledging the past. Bajío (Lowland) corresponds to a small fragment of the Paraná Delta, an exceptionally biodiverse landscape in eastern Argentina that lies near the country’s largest metropolitan areas (cat. 40). The Paraná Delta faces irreversible ecological change due to urban growth, unsustainable agricultural practices, and the consequences of climate change. The carpet is especially personal, as it documents an island in the Paraná wetlands where Kehayoglou lived with her family during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Kehayoglou’s connection with her homeland, however, is both natural—drawn from the landscape—and man-made, a product of her family’s multigenerational manufacturing presence in Argentina. Kehayoglou’s family has operated a factory that has been making industrial carpets for more than sixty years. In this way, her work represents the reciprocal dynamics of human ecology theory. Both halves come together as Kehayoglou re-creates ephemeral native landscapes with a physical manifestation of her family’s history. Tuan’s concept of topophilia exemplifies the complex dynamic of Kehayoglou’s artistic practice: “the affective bond between people and place or setting. Diffuse as concept, vivid and concrete as personal experience.”5

Spanish artist and designer Nacho Carbonell’s One-Seater Concrete Tree pays tribute to the sun-soaked Mediterranean landscape of his childhood home (cat. 8). Born in Spain, Carbonell spent his formative years with his family in Valencia before moving to Eindhoven in 2005 to pursue his studies. It was only after leaving Valencia that Carbonell discovered the fundamental role the region’s natural environment played in shaping his identity. In response, Carbonell created a body of work that explores his memories of the geography that defines his previous home, from the picturesque Mediterranean coastline to the rugged mountain ranges. Carbonell explains the influence of these natural elements: “I just take them, and I appropriate them because they are part of me, and I use them. I feel entitled to say, ‘Okay, because we grew together, I can use you in my work to create this narrative for others, to let them know that you exist here.’”6

One-Seater Concrete Tree is a large-scale light sculpture shaped as a sinuous tree. Its highly textured, bulbous metal mesh canopy appears to have organically sprouted from the rugged concrete seat designed for one person. Organic and tactile, One-Seater Concrete Tree possesses a vitality that suggests a living organism, achieved through Carbonell’s use of various textures and man-made materials such as metal mesh, steel, and concrete. As viewers take a seat, the functional sculpture comes alive, arousing their imagination and transporting them to the semiarid Mediterranean landscape that Carbonell vividly remembers, or perhaps triggering memories of their own. Carbonell clarifies, “I want them to look at their own context, to open the door and they are able to see that beauty exists in any other part of the world. We only need to look outside.”7 Ultimately, Carbonell’s artistic vision is an emotional response to his own past, expressed through experimental forms and materials. Drawing from his cherished memories of his family home, he has created a tactile and functional self-portrait, which serves as a physical manifestation of the natural beauty that characterizes eastern Spain.

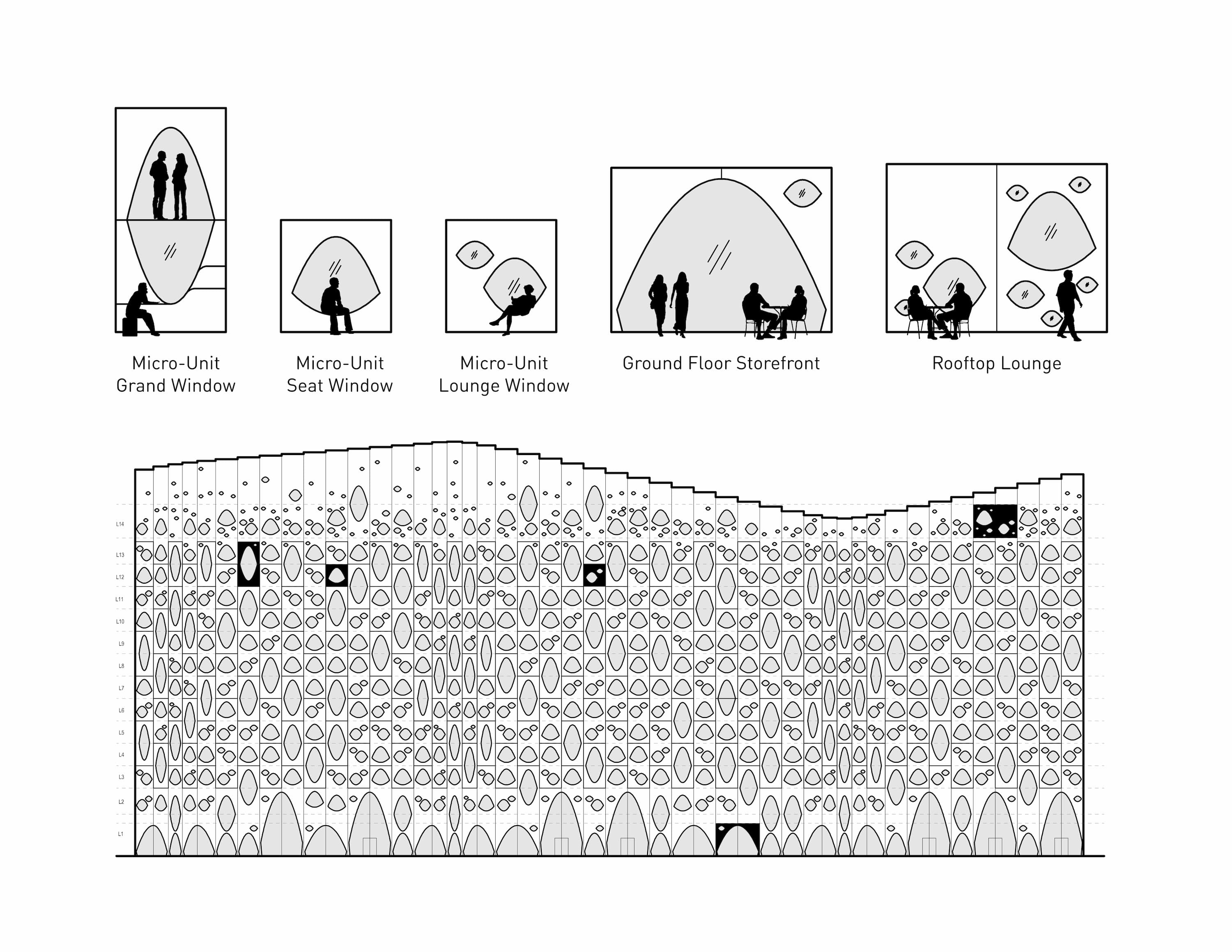

Located in downtown Denver, Studio Gang’s Populus evokes the alluring features of a stand of aspen trees (cats. 85 and 83). The architecture and urban design practice’s thirteen-story, 135,000-square-foot hotel takes its name from Populus tremuloides, commonly known as quaking aspen, which is the most widely distributed tree in North America and an instantly recognizable symbol of Colorado. The texture and rhythm of the hotel’s sculptural facade are strongly tied to its function. A series of forty-six thin vertical scallops, each as wide as a typical guest room, envelops the entire structure. Five distinctive window types, from dramatic ground-level arches to smaller openings, punctuate the hotel’s exterior surface. Their unique shapes are inspired by the distinguishing patterns found on aspen trunks. As the trees grow, they shed their lower branches, leaving behind peculiar eye-shaped marks on their thin, papery bark. The windows are also designed to respond to the interior spaces and functions. Some rooms feature windowsills that integrate seating or desks, while at the building’s base, thirty-foot-high openings frame entrances and provide views into public spaces. As Finnish architect Juhani Pallasmaa once remarked, “Architecture is essentially an extension of nature into the man-made realm.”8 Studio Gang’s Populus captures the essential attributes of a serene grove of majestic, straight, white-barked aspen trees, right in the heart of the city of Denver.

Completed in 2021, the Nanjing Zendai Himalayas Center by Beijing-based MAD Architects combines urban life with the emotional resonance of shan shui, a traditional style of Chinese landscape painting. Shan shui paintings often depict misty mountains and flowing rivers with delicate brushwork to convey a sense of tranquility and contemplation. The goal of shan shui painting is not to create a realistic representation but to capture the essence and spirit of the natural world. It is not important whether the painted colors and shapes look exactly like the real object.

Located in the capital of China’s eastern Jiangsu province, the Nanjing Zendai Himalayas Center is a 138-acre urban development consisting of commercial, hotel, office, and residential spaces (cats. 70 and 71). The complex is made up of thirteen mountainous towers intended to evoke a natural Chinese landscape. Placed along the edge of the site, the lofty structures are delineated by their vertical white glass fins that flow like waterfalls. The development’s elevated vertical park features meandering pathways that serve as an invitation for people to wander among water features, gardens, and buildings. At the center of the site is a village-like community of low buildings, connected by footbridges and nestled into the landscape. By bringing people up from the busy street level, MAD has created an inviting landscape integrating the different elements (fig. 5).

The Nanjing Zendai Himalayas Center seeks to challenge the prevailing typology of rectangular, homogenous, linear structures that have shaped our urban environment. In describing cities as “steel concrete forests,” MAD suggests that our urban environments fail to match the thriving ecosystem of a forest and argues that a forest requires a state of symbiosis between every organism.9

In today’s increasingly urbanized and globalized world, the concept of topophilia takes on renewed significance. As individuals and communities become more disconnected from the natural environment and uprooted from their traditional homelands, the need for a sense of place and belonging grows stronger. Topophilia offers a framework for understanding and nurturing our emotional connection to the physical spaces we inhabit. It reminds us of the profound impact that our surroundings have on our well-being, identity, and sense of rootedness. By exploring the diverse manifestations of topophilia through art, design, and architecture, we can foster a deeper appreciation for the places we call home and cultivate a more sustainable and harmonious relationship with our environment.

-

Yi-Fu Tuan, Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes, and Values (New York: Columbia University Press, 1974). ↩︎

-

Tuan, Topophilia, 247. ↩︎

-

Historically, the Tohono O’odham inhabited an enormous area of land in the Southwest, extending south to Sonora, Mexico, north to central Arizona, west to the Gulf of California, and east to the San Pedro River. This land was known as the Papagueria, and it had been home to the O’odham for thousands of years. Today, the federally recognized Tohono O’odham Nation occupies 2.8 million acres of tribal land within the Sonoran Desert in south central Arizona. Official Web Site of the Tohono O’odham Nation, accessed August 8, 2023, http://www.tonation-nsn.gov. ↩︎

-

Anna Carnick, “Alexandra Kehayoglou on Design & Nature,” Design Miami, September 24, 2021, https://shop.designmiami.com/blogs/news/alexandra-kehayoglou-on-design-nature. ↩︎

-

Tuan, Topophilia, 4. ↩︎

-

Carpenters Workshop Gallery, “Nacho Carbonell’s Inaugural Exhibition for Carpenters Workshop Gallery in Los Angeles,” September 26, 2022, video, 2:08, https://youtu.be/yWQr6jebkrQ. ↩︎

-

Ibid, 2:29. ↩︎

-

Juhani Pallasmaa, The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2012), 44. ↩︎

-

“MAD Architects: Absolute Towers Completed,” Designboom, December 12, 2012, https://www.designboom.com/architecture/mad-architects-absolute-towers-nearing-completion/. ↩︎