Natural systems describe nature’s processes and phenomena, especially seasonal and temporal changes characteristic of a healthy ecosystem, such as climate and weather patterns, hydrology, and plant receptivity and cycles. Social ecologist Stephen Kellert, whose research and writing advanced the understanding of the connection between humans and the natural world, pointed to biophilia as “the inherent human inclination to affiliate with natural systems and processes, most particularly life and life-like (e.g., ecosystems) features of the nonhuman environment.”1 There is limited, but growing, scientific documentation of the health impacts associated with access to natural systems. These systems, or at least their observable characteristics, are believed to enhance positive health responses. Kellert acknowledged that seeing and understanding the processes of nature can create a perceptual shift in what’s being seen and experienced.2 This relationship has a strong temporal element, as seen in Japanese culture’s celebration of the ephemerality of cherry blossoms and some Indigenous cultures’ view of auroras as the spirits of ancestors or celestial dancers.

Over the past twenty years, technology has greatly reshaped our world and our relationship to it. The proliferation of technological achievements, like the rapid advancements in artificial intelligence, continues, distracting us from other relationships, including our connection with natural systems. But what if it could reconnect us instead? It is perhaps no surprise that the use of cutting-edge technologies to manifest the wonders of nature is burgeoning among contemporary artists and designers who meditate on how humans and the natural world are intricately intertwined and interdependent.

The following artworks go beyond making use of nature’s forms or patterns to evoke the natural rhythms of life—the fundamental exchange of energy between organisms and their environments. These experiences create meaningful, direct connections with natural processes and phenomena, particularly through movement and other multisensory interactions. They invite us to slow down, pay attention, and trust what our bodies already understand. In doing so, they foster a relationship with a greater whole, triggering a deeper awareness of the nature of life and the sense of awe and wonder we can experience when immersed in it. While they are not a replacement for the real thing, these encounters can cultivate surprise, delight, and even empathy. They may even inspire stewardship of the ecosystems within which we all exist.

Cofounded by artists Lonneke Gordijn and Ralph Nauta, the Amsterdam-based multidisciplinary practice DRIFT creates experiential sculptures, installations, and performances that reawaken our connection to the natural world. DRIFT manifests the phenomena and hidden properties of nature with the use of technology to reestablish our connection to it. “DRIFT reconnects people with nature through art,” according to Nauta. “We create spaces where the viewer is tuned into rhythms resembling natural movements such as the blossoming of flowers, flocks of flying birds, and sea waves.”3

DRIFT’s Shylight and Meadow examine how a man-made object can mirror and amplify nature’s subtle wonders (fig. 1 and cat. 14). The kinetic installations feature mechanical flowers made from layers of diaphanous silk, and integrated LED lights illuminate them from within. Suspended from above, each fixture is programmed to mimic the nastic movement of blossoms that open and close in reaction to changing light. Shylight and Meadow emulate the biological behavior of nyctinasty but do not strictly copy it. Going beyond mere imitation, DRIFT’s flowers are oversized, and the speed of their movement is accelerated. The results give the impression of experiencing the phenomena under a magnifying glass and at a quickened pace.

Produced in 2006, Shylight features white flowers that descend and unfurl to bloom above the viewer’s head, before retreating upward and closing again (fig. 2). The installation’s ethereal appearance contradicts the complex technical components and custom software that took DRIFT years to develop. Shylight feels alive due to its carefully choregraphed movements that are based on natural human rhythms, such as heartbeats and breathing. While the blossoms in Shylight appear to move individually and independently from one another, Meadow could be understood as a single organism—an interconnected field of colorful flowers that perpetually open and close in sequence. Meadow’s rhythmic and persistent change awakens not only the senses but also the imagination, as it delves into the uncanny nature of a sentient environment. We experience Meadow more like we see ourselves: with character, body language, and a collective story.

Meadow’s fabric flowers are printed in gradient shades that harmonize with colored LED lights to evoke the changing tones of a skyscape as dawn transitions to dusk. Its unique colors and ever-changing choreography imbue the artwork with an organic beauty. According to DRIFT, the artwork is “inspired by the impermanence of the ever-changing seasons, the sensational character of natural growth processes, and the insight that plant life often functions as a colony, rather than as a group of individuals.”4 Meadow evokes the ephemerality of nature and the sense of awe that comes from being enveloped by it.

Although Meadow evokes nyctinasty, its choreography can be described as a Heraclitean motion, a soft pattern of movement associated with safety and comfort that “is always changing but always remaining the same,” like waves lapping on a shore or grass rippling in the breeze (fig. 3).5 As both a constantly changing light source and a field of mechanical blossoms, Meadow captures our attention effortlessly. The overall effect encourages “soft fascination,” allowing the mind to relax and recover while watching the hypnotic motion of the lamps.6 The cathartic, quiet pace of Meadow invites us to collectively explore the complexities of the natural world.

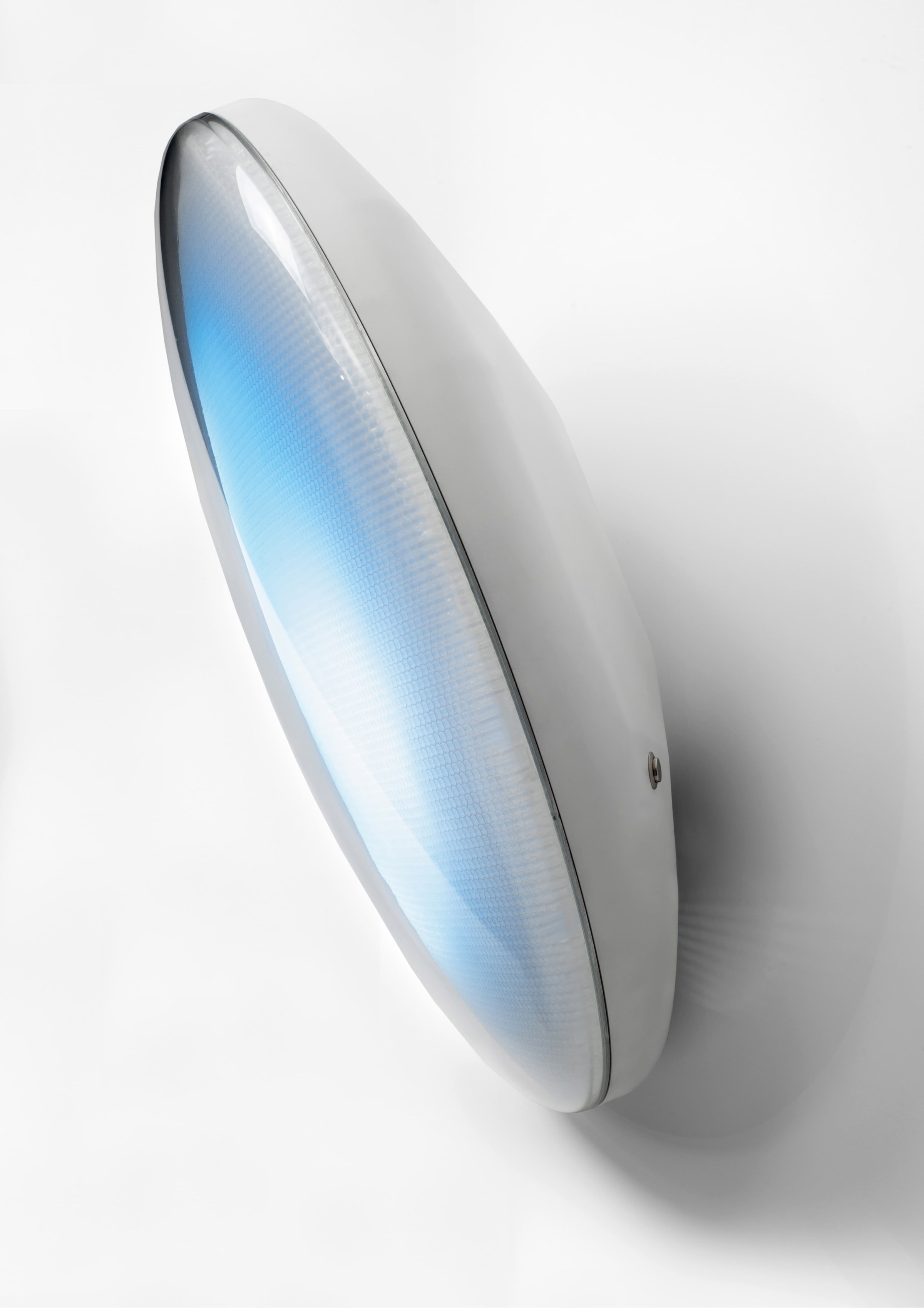

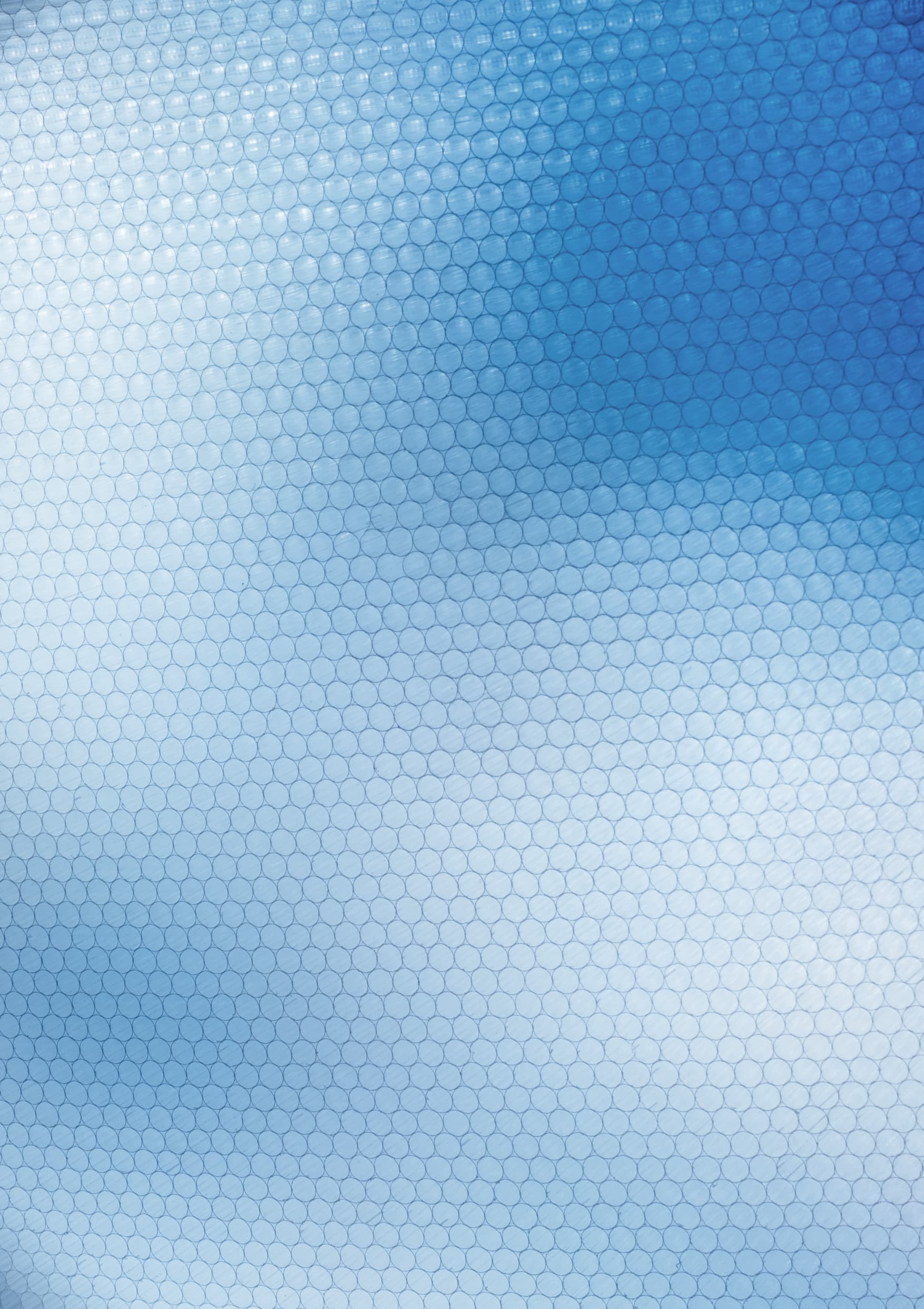

French multidisciplinary designer Mathieu Lehanneur combines art, design, science, and technology in projects that interpret natural systems and replicates them into human-centered solutions that benefit society. Originally conceived for the palliative care unit at the Diaconesses Croix Saint-Simon Hospital Group in Paris, Lehanneur’s Tomorrow Is Another Day (Demain est un autre jour) generates a digital animation of tomorrow’s sky (cat. 61). Installed on the wall of a patient’s room, Tomorrow Is Another Day broadcasts a slowly and continuously moving image of the atmosphere through its circular screen. “It’s not a video that plays the same images of the same sky over and over again,” Lehanneur explains.7 The designer worked with a computer programmer to create custom software that aggregates meteorological and atmospheric data, such as the time of day, color of the sky, speed and transparency of clouds, and humidity, from the internet in real time to create an animation of tomorrow’s sky. The aperture can be customized to reflect specific locations, providing a sense of familiarity and personalization.

Lehanneur’s concept purposely fosters a profound therapeutic and poetic experience for the patients who observe it, aiming to reestablish their connection with the ever-changing weather patterns of the natural world. According to Lehanneur, “There were infinite variations of grays, cloudy silhouettes, and light intensity that had to be reproduced. Paradoxically, it was necessary to reach this level of sophistication so that the patient could let their mind go, as if lying in a field, eyes turned to the sky.”8 It’s a reminder that no two clouds or skies are ever the same.

These vital aspects of nature often remain concealed from patients and other individuals in healthcare facilities, yet passive visual experiences hold the potential to offer profound benefits through diverse encounters with nature. Stress recovery theory (SRT) proposes that contact with natural environments reduces the psychophysiological stress level of individuals, while attention restoration theory (ART) suggests that mental fatigue and concentration can be improved by time spent in, or looking at, nature.9 Tomorrow Is Another Day not only captures these elusive natural phenomena but also transforms them into spiritual experiences for patients and their families. It prompts contemplation on the concepts of permanence and impermanence, the fundamental principles of uncertainty, and spirituality. Ultimately, the artwork offers a unique opportunity to transcend the confines of time itself.

Works like Lehanneur’s Tomorrow Is Another Day, DRIFT’s Meadow, or J. MAYER H.’s Metropol Parasol (see “Natural Analogs”) conjure dynamic and diffuse natural light conditions that change from moment to moment because of varying atmospheric conditions or the fluttering of leaves in a canopy of a stand of aspen trees.10 The fractal patterns of light and shadow on a surface are an expression of time and motion that can attract our attention, evoke a sense of calm, and help connect us with the rhythms of life.

London-based Dutch artist Simon Heijdens reinterprets natural processes with unique technologies, embedding them in man-made surroundings to uncover the hidden essence of a place. Meteorological conditions, including sunlight and wind, along with custom algorithms and human interactions, dynamically transform the artist’s responsive artworks in real time, giving rise to ever-changing forms. Despite their technical complexity, Heijdens’s installations possess a restrained and poetic appearance, seamlessly integrated into their respective settings. They provoke contemplation on the significance of nature and coincidence in an increasingly developed world while offering moments of exploration, wonder, and introspection.

Heijdens’s Lightweeds is a living digital organism that reintroduces us to nature’s element of surprise (cat. 34). These virtual plants grow indoors but depend closely on actual rain and sunlight, swaying with the wind. Lightweeds responds in real time to the ever-changing weather conditions of the outside world, as measured through sensors placed on the exterior of the building or obtained through live online weather data. As people pass by, the willowy weeds shudder and sway, eventually pollinating. Their seeds trail passers-by before dispersing throughout the space. With their continuous cycle of growth and decay, the plants’ location and density reveal insights into the way the building is utilized.

Lightweeds not only chronicles the passage of time but also captures the evolution of the natural surroundings. Generated from a specific locality and in a state of constant flux, the digital projection introduces an element of chance and time into the built environment. By doing so, it unveils the natural processes and phenomena that are gradually disappearing from our increasingly conditioned, static, and climate-controlled urban lives. Lightweeds serves as a visual reminder to reengage with the inherent beauty and vitality of the natural world that surrounds us.

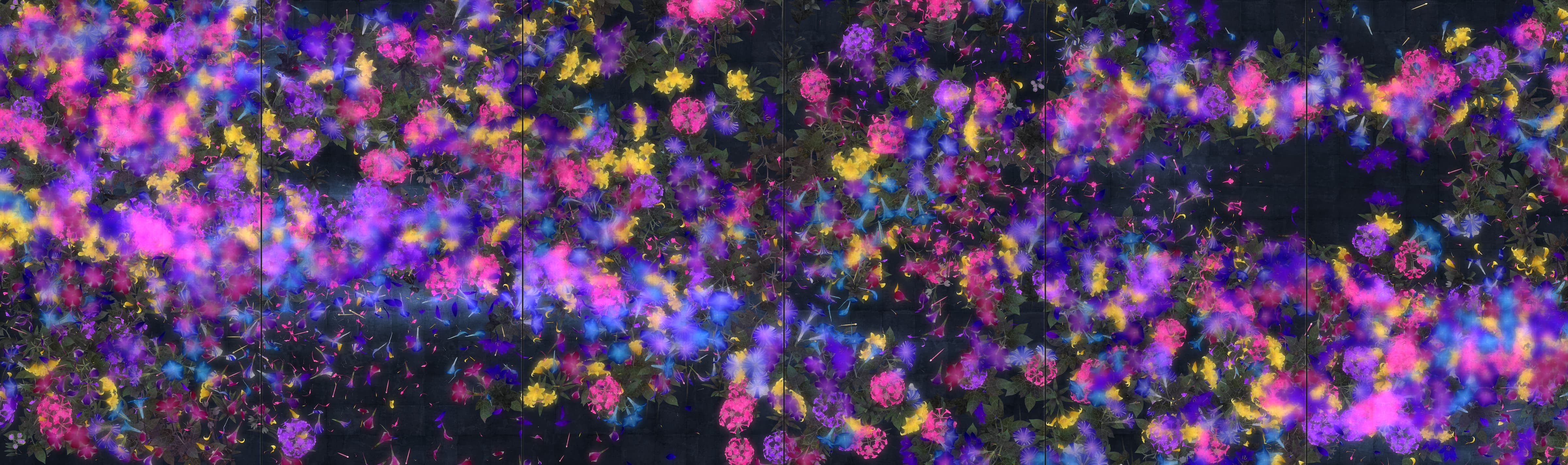

Flowers and People – A Whole Year per Hour addresses the fleeting nature of the seasons and the interactional relationship between humans and the natural world (cat. 92). The interactive digital artwork vividly depicts a year’s worth of seasonal flowers that continuously change. The flowers gradually and repeatedly sprout, grow, bud, and blossom until their petals eventually scatter and fade across the artwork’s multiple screens. The cycles of growth and efflorescence advance through spring, summer, fall, and winter at an accelerated pace. As the title suggests, one year passes in the span of an hour.

Created by teamLab, a Tokyo-based art collective including artists, programmers, engineers, CG animators, mathematicians, and architects who collaboratively navigate the confluence of art, technology, design, and the natural world, Flowers and People is generated by a computer program that continuously presents the work so that no two moments are the same, and the interaction between people and the artwork causes continuous changes. When people move in front of the screens, the flowers’ petals scatter. But when they stand still, flowers grow and bloom more profusely. The surreal, yet sensuous, components of Flowers and People form an artificial ecosystem, gently flexing and responding to time and the viewer, that can never be replicated. People become active participants, cocreating and establishing collective resonance.11 This approach casts visitors and their relationships to one another as integral to the ultimate form of the work—underscoring their collective presence as a positive means of creation and serving as a metaphor for the integrated systems of nature itself, where distinctive parts interact to become a unified whole (cat. 92 detail).

Long fascinated by humans’ engagement with the natural world, teamLab wants people to see in real time their impact on nature. “Rather than nature and humans being in conflict, a healthy ecosystem is one that includes people,” teamLab explains. “In the past, people understood that they could not grasp nature in its entirety, and that it is not possible to control nature. People lived more closely aligned to the rules of nature that created a comfortable natural environment . . . . We hope to explore a form of human intervention based on the premise that nature cannot be controlled.”12 Flowers and People heightens the participants’ awareness of the world they inhabit and can inspire a reconsideration of their own impact upon shared ecosystems. In an increasingly divisive world in which feelings of alienation and isolation are replacing those of relationship and community, such experiences are fundamental to our well-being.

In an era dominated by technology and a growing disconnection from nature, it is crucial to find ways to reconnect with the natural world. The use of cutting-edge technologies in art and design offers a unique opportunity to bridge this gap and evoke a sense of wonder and awe through engaging experiences. Artists and designers utilize technology to manifest the beauty and intricacies of natural systems, reminding us of our inherent connection to the environment. These artworks invite us to slow down, pay attention, and engage with the rhythms of life. By experiencing these digital interpretations of nature’s systems and processes, we can cultivate a deeper appreciation and understanding of the ecosystems that surround us, fostering a sense of stewardship and inspiring positive change. Through art, technology, and our own active participation, we have the power to rekindle our relationship with the natural world and forge a harmonious future.

-

Stephen R. Kellert, “Biophilia,” in Encyclopedia of Ecology, ed. Sven Erik Jørgensen and Brian D. Fath (n.p.: Elsevier B. V., 2008), 462. Since the 1990s, the concerns of biophilia theory have shifted from its initial focus on life or living organisms to exploring the relationship between humans and the natural environment. ↩︎

-

Stephen R. Kellert, Judith Heerwagen, and Martin Mador, eds., Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2011). ↩︎

-

TDE Editorial Team, “Design Duos / DRIFT,” The Design Edit, September 9, 2021, https://thedesignedit.com/people/design-duos/design-duos-drift. ↩︎

-

Katy Donoghue, “Meadow by DRIFT: The Poetic Installation Engaging Visitors at Superblue,” Whitewall, December 1, 2021, https://whitewall.art/art/meadow-by-drift-the-poetic-installation-engaging-visitors-at-superblue. ↩︎

-

Aaron Katcher and Gregory Wilkins, “Dialogue with Animals: Its Nature and Culture,” in The Biophilia Hypothesis, eds. Stephen R. Kellert and Edward O. Wilson (Washington, DC: Island Press, 1993), 176. ↩︎

-

Rachel Kaplan and Stephen Kaplan, The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1989). A core premise of Rachel and Stephen Kaplan’s Attention Restoration Theory (ART) suggests that mental fatigue and concentration can be improved by time spent in, or looking at, nature. There are certain types of restorative experiences that seem to transcend others and produce multiple benefits, not just the benefit of escape from stress alone. One of these states is the “soft fascination” that occurs when a person is immersed in nature, a stimulus that initiates the use of involuntary attention, or attention that requires no effort. ↩︎

-

Celia Sampol, “Spotlight on a Spiritual Work Questioning Time Dedicated to Palliative Care,” E-Magazine by MedicalExpo, July 11, 2022, https://emag.medicalexpo.com/spotlight-on-a-spiritual-work-questioning-time-and-dedicated-to-palliative-care/. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Roger S. Ulrich, Robert F. Simons, Barbara D. Losito, Evelyn Fiorito, Mark A. Miles, and Michael Zelson, “Stress Recovery during Exposure to Natural and Urban Environments,” Journal of Environmental Psychology 11, no. 3 (1991): 201–30, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(05)80184-7; Stephen Kaplan, “The Restorative Benefits of Nature: Toward an Integrated Framework,” Journal of Environmental Psychology 15, no.3 (September 1995): 169–82, https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-4944(95)90001-2. ↩︎

-

William Browning, Catherine Ryan, and Joseph Clancy, 14 Patterns of Biophilic Design: Improving Health & Well-Being in the Built Environment (New York: Terrapin Bright Green, 2014), https://www.terrapinbrightgreen.com/reports/14-patterns/. ↩︎

-

Collective resonance has been defined as “a felt physical and energetic sense of connection that occurs in a group of human beings that positively influences the way they interact toward a common purpose.” Renee A. Levi, “Group Magic: An Inquiry into Experiences of Collective Resonance” (PhD diss., Saybrook Graduate School and Research Center, 2003), 2. ↩︎

-

teamLab, “Flowers and People, Cannot be Controlled but Live Together—Dark,” accessed April 29, 2024, https://www.teamlab.art/w/flowerandpeople-together-dark/movinglight-rovingsight/. ↩︎