Throughout history, architects, artists, and designers have turned to nature as a source of inspiration and solace during challenging times and periods of societal crisis, seeking to find harmony, connection, and meaning in the world. The Arts and Crafts movement in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries emerged as a response to industrialization and urbanization. The movement sought to revive traditional craftsmanship and celebrate the beauty of natural forms. Similarly, the mid-twentieth-century organic design movement was influenced by a desire to create more harmonious relationships between humans and their environment, countering the still lingering negative effects of industrialization.

The idea that nature can serve as an antidote to technology is a perspective that many people have held over the years. This perspective often arises from concerns about the potential negative effects of technology on various aspects of human life and society. But many designs inspired by nature benefit from the use of technology to replicate or adapt natural forms and structures. These designs often result in highly efficient, structurally logical, and innovative products, systems, or solutions. This concept remains an influential force in shaping contemporary art and design, offering new responses to our relationship with the natural world.

Natural analogs in architecture, art, and design evoke naturally occurring forms and patterns and aim to establish connections between humans and the natural world.1 Architects, artists, and designers simulate nature’s boundless shapes, structures, and organizing principles, expressed in a broad spectrum of forms and functions, from appropriating biomorphic forms to mimicking nature’s underlying geometries and growth processes.

The following works from the fields of architecture, art, and design do not simply imitate nature but use it as a starting point for eclectic and innovative responses to our relationship with our environment. They highlight the uniqueness and dynamism that nature’s forms and patterns have to affect us, tapping into our intimate, emotional, and spiritual connections with the natural world. Natural analogs foster a deeper appreciation for nature’s aesthetics, stimulate feelings of wonder, and promote a sense of responsibility for preserving and coexisting with the natural environment.

Form

The appropriation of diverse natural forms can lead to the creation of aesthetically pleasing and emotionally satisfying objects. By capturing the beauty of nature in fixed form, artists and designers create captivating environments and imbue spaces with a sense of tranquility and wonder. While our brain knows that these objects are not living things, we describe them as symbolic representations of life.2

Sandra Davolio’s delicately handcrafted porcelain vessels take inspiration from the organic structures of coral typically found in the sunlit shallows of tropical seas. Achieving a diversity akin to their real-life counterparts, no two works are alike. Paperlike in texture, Coral Flower IV fans outward with organic ripples, its unglazed exterior retaining a finish and texture reminiscent of coral fragments washed onto the shore (cat. 10). Similarly, Ronan and Erwan Bouroullec’s Algues (Algae) take cues from the diverse organisms that play crucial roles in our aquatic ecosystems (cat. 5). The interlocking plastic modules can be assembled into endless configurations to form partitions of varying sizes and densities, allowing light to filter through their lacy structure like algae’s captivating translucency.

David Valner’s Fungus vases and bowls conjure the peculiar forms found in the fascinating world of fungi: from delicate and elongated stalks to intricate and convoluted caps. Valner employs traditional glass making techniques to create these functional objects (cats. 96–107). Their glass surfaces simulate the variable and complex colors observed on fungal bodies found in the damp recesses beneath our feet. Meanwhile, Front’s Curve Lamps appear to grow and adapt to their surroundings. The fixtures reimagine the iconic green-glass banker’s lamps with a contemporary twist (cats. 19–25). Emerging from small yet sturdy bases, the lights stretch and bend upward like a plant or mushroom sprouting from the forest floor, seeking the nourishing rays of the sun.

Andrés Reisinger and Júlia Esqué’s Hortensia Armchair is an exuberant interpretation of hydrangea flowers in bloom (cat. 82). Initially conceived as a digital piece of furniture by Reisinger, the chair was brought to life with Esqué, a textile designer. Upholstered with over 30,000 laser-cut pink polyester petals, the limited-edition chair evokes the feeling of sitting in a blooming flower. Fernando and Humberto Campana’s Bulbo conjures the mysterious tropical flora of the brothers’ native Brazil (cat. 7). The layered petals of the flower-shaped seat gently cradle the sitter to provide a feeling of security and tranquility.

Crafted by master glassblowers, Andreea Avram Rusu’s Botanica Chandelier resembles the weighty and sculptural blossoms of banana plants in milky pastel hues (cat. 4). The surreal composition—large, pendulous flowers and a series of overlapping leaves suspended from stems wrapped with leather—dynamically responds to the interplay of surrounding light. While Avram Rusu expresses her fascination with plant life in glass form, the lush banana fronds of PELLE’s eye-catching Nana Lure Chandelier are made of cast cotton paper (cat. 81). Illuminated from their undersides, the large, elongated leaves are sculpted and painted by hand. Each leaf is depicted with the accuracy of a botanical illustration, from the prominent vein that runs their length to the gentle wavelike pattern of their weathered edges.

Marc Fish’s Ethereal Double Console is made of paper-thin veneers of sycamore, which are laminated and manipulated into organic twists and curves and held together with translucent resin (cat. 15). By preserving the order of the veneers as they would be in the tree, the console appears as if the wood itself has grown into its shape. The innovative results resemble the lacy translucency of a skeletal leaf.

Fredrikson Stallard’s Species 1 expresses the chaotic energy of the earth’s geological processes (cat. 16). Made from a block of polyurethane foam, the hand-carved sofa appears to have been shaped by natural phenomena such as tectonic movements and erosion over an immense period of time. Species 1 suggests natural places to perch or recline, yet it resists mirroring the human body. Only when activated by a sitter does the functionality of the sofa’s form emerge. Similarly, their Rock #22 and Rock #23 appear to be extracted from the earth’s surface but are, in fact, remnants from the production of the Species series (cats. 17 and 18). Supported by steel mounts, the sculptural objects resemble rock, mineral, or meteorite specimens in a natural history museum or a cabinet of curiosities.

Pattern

Patterns are a fundamental aspect of the natural world, and they can take on a wide range of forms, from the highly visible and repetitive to the subtle and chaotic. These patterns often emerge as a result of natural processes, physical laws, and interactions among various elements in the environment, but not all are visible to the naked eye. They often require microscopes, mathematical models, and visualizations for us to observe and understand them. Architects and designers often find inspiration in these diverse patterns to create visually captivating and conceptually profound structures.

In his renowned book from 1979, The Sense of Order, Austrian art historian Ernst Gombrich delves into the psychological aspects of human perception and appreciation of decorative art.3 Gombrich seeks to unravel the underlying reasons behind our fascination with and inclination toward order, symmetry, and geometric patterns in artistic expressions throughout various cultures and historical periods. He argues that the human mind possesses an inherent “sense of order,” which drives our artistic creativity and preferences. This sense of order can be traced back to our evolutionary history, where the ability to identify patterns and regularities in the environment conferred survival advantages. As a result, the human brain developed a natural affinity for finding and creating order in the chaotic world. It is not just a study of art and aesthetics but an exploration of human psychology and cognition. By understanding the psychological foundations of our appreciation for order and symmetry, Gombrich sheds light on the fundamental aspects of human behavior and culture.

Fractals, in particular, seem to capture the human imagination. Fractals, a term coined in 1975 by the mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot, have effectively quantified the intricate underlying patterns found in many natural objects.4 Fractals are infinitely complex patterns, or mathematical forms, that exhibit self-similarity across different scales. When we look at a fractal, we often see intricate, repetitive patterns that continue to appear at different scales. Mandelbrot argued that fractals and fractal-like patterns that emerge during natural growth processes can be found in various natural phenomena, ranging from the micro- to the macroscale. These include vein patterns in leaves, the branching structure of trees, mountain ranges, river networks, coastlines, waves, and even cloud formations. The examples are nearly limitless. Described as both the “fingerprint of nature”5 and “the new aesthetics,”6 fractal patterns and forms have captured the imaginations of scientists and artists alike.

Fractals, among other geometrical patterns, have been proven to reduce physiological and emotional stress in humans, playing a significant role in evolutionary aesthetics and environmental psychology.7 Research consistently demonstrates correlations between fractal dimensions in nature and those in architecture, art, and design.8 As humans, we display a consistent aesthetic preference for fractal images, whether or not these images are generated by nature’s processes, mathematical equations, or human creativity.

Fashion design collective threeASFOUR’s Human Plant collection explores the beauty and complexity of fractal-like structures found within the plant world (cats. 93–95). Employing laser cutting, pleating, and other techniques, the studio creates exquisite plantlike details and textures. Patterns based on the complex network of leaf veins that branch and intersect are printed on skirts, pants, and jackets that wrap the body, such as Autumn Leaf Suit. Cut-out dresses, including Eve Dress, are assembled piece by piece out of components that mimic the intricate network of veins found in some leaves. The parts are laser cut, seemingly leaving behind only the leaves’ structural support. Another ensemble, Lily Dress, captures the aquatic plant’s distinctive circular leaves that rest on the water’s surface. The collection beautifully evokes the harmonious geometries of nature’s abundant foliage. By magnifying these diminutive patterns and distinct structures, threeASFOUR establishes an intimate connection between these geometries and the human body. Ultimately, Human Plant prompts us to look more closely and cherish the mesmerizing details that govern nature’s beauty that often go unnoticed by the human eye.

Within the densely packed urban fabric of Seville, Spain, stands Metropol Parasol, a massive one-hundred-foot-high undulating structure designed by Berlin-based architecture firm J. MAYER H. (cat. 37). The structure’s six large timber columns rise from a concrete base to form a dendritic-like canopy that provides shade for the city’s historic Plaza de la Encarnación. The parasols are constructed from an interweaving waffle-like timber lattice that creates continuously shifting shadows throughout the day (cat. 39). The structure creates a distinctive public space that offers shelter and areas to gather and evokes the sense of being under a forest canopy. Its public, open-air spaces feature permeable boundaries and provide spatial freedom reminiscent of nature while fostering a distinct sense of place within the city’s dense historic center. By employing tree, or mushroom, metaphors architecturally, Metropol Parasol achieves a dual purpose: expressing a lamentation for nature’s absence and symbolically inserting its presence.

Besides the wonders of plant structures, another remarkable, clearly visible manifestation of fractals is the ocean and its complex types of waves.9 Mathieu Lehanneur’s Ocean Memories captures the ripples and shimmers of ocean waves in fixed form (cat. 44). The collection of tables, benches, and stools resembles the captivating surface of the ocean and demonstrates how modern technology can be harnessed to mimic the fluid dynamics of waves as they rise and fall. Lehanneur and his team employed 3-D special effects software typically used by the film industry to reproduce the complex geometry and movement of water into digital forms. Blocks of marble were then machine cut to replicate the digitally created patterns, before being hand polished to a glossy, liquid-like finish to create a surface that is as reflective as the ocean. Ocean Memories captures a surrealistic vision of an ocean frozen in time, reminding us of the immense power and beauty of nature.

Iris van Herpen’s collection Sensory Seas dives into the marine ecology that thrives deep within the ocean (cat. 109). Suggesting the intricate and organic structures found in the mysterious regions of our aquatic environments, the Diatom Gown features translucent cellular patterns of what could be described as the exoskeletons of microalgae. Inky blues and greens are printed onto sheer silk organza and layered organically, forming a sea of fibrous structures. The dress evokes the ebb and flow often associated with underwater life (fig. 1). With its fluttering fabrics, use of color, and fantastic pattern, the dress holds a microscope above the ethereal marine world and the mesmerizing microorganisms it holds.

In today’s computational world, architects and designers often utilize generative design approaches that leverage algorithms, simulations, and iterative processes to simulate complex biological phenomena or physical occurrences found in the natural world. In the latter part of the twentieth century, the quest to replicate nature’s creative code took an astounding new turn. The simulation of nature’s almost inexpressible patterns became possible through emerging computational technologies, such as generative, parametric, and algorithmic design tools. Geometries that were once extremely challenging or even impossible to fabricate are now realized with advanced computer-assisted production methods known as digital fabrication.

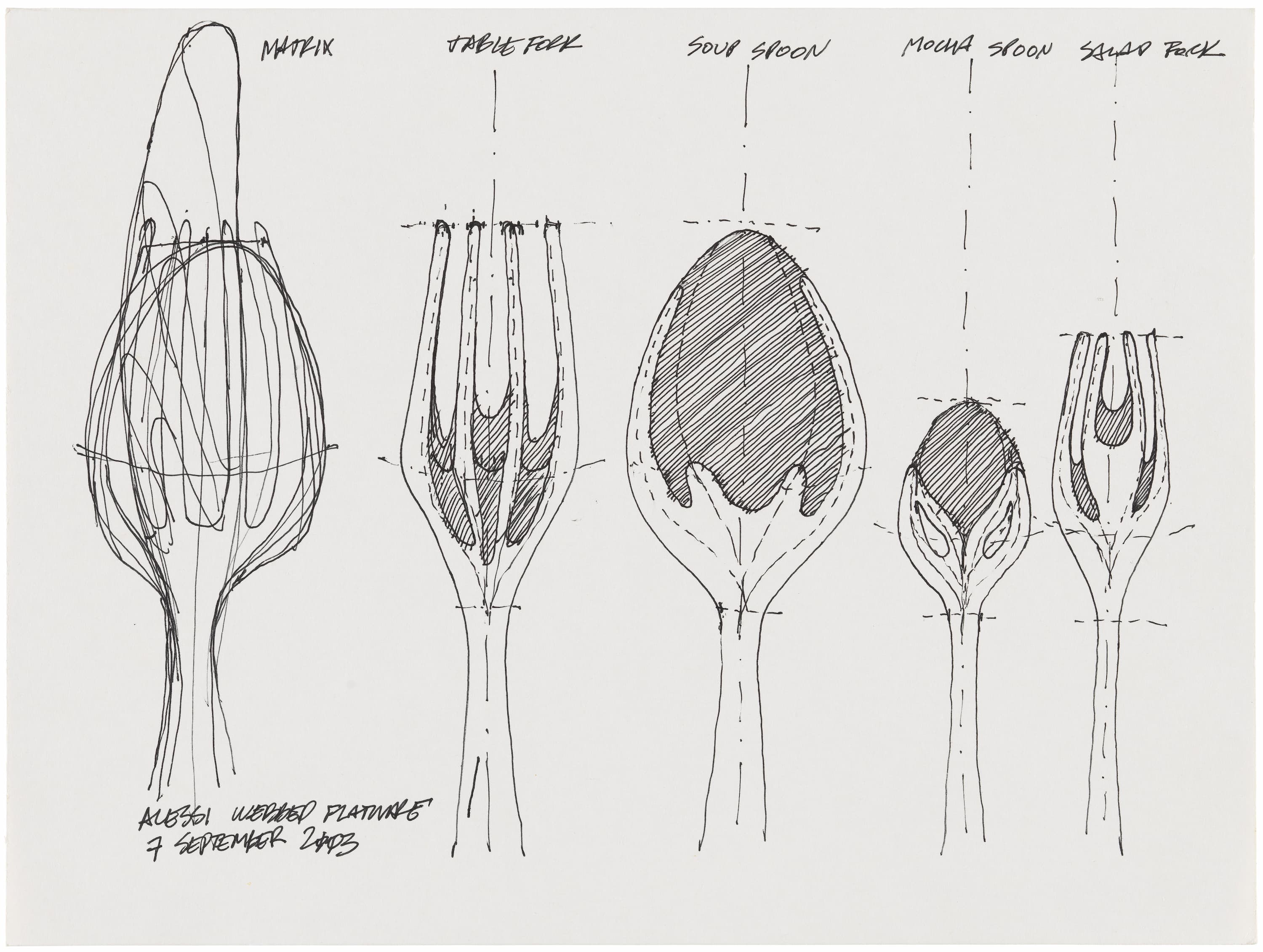

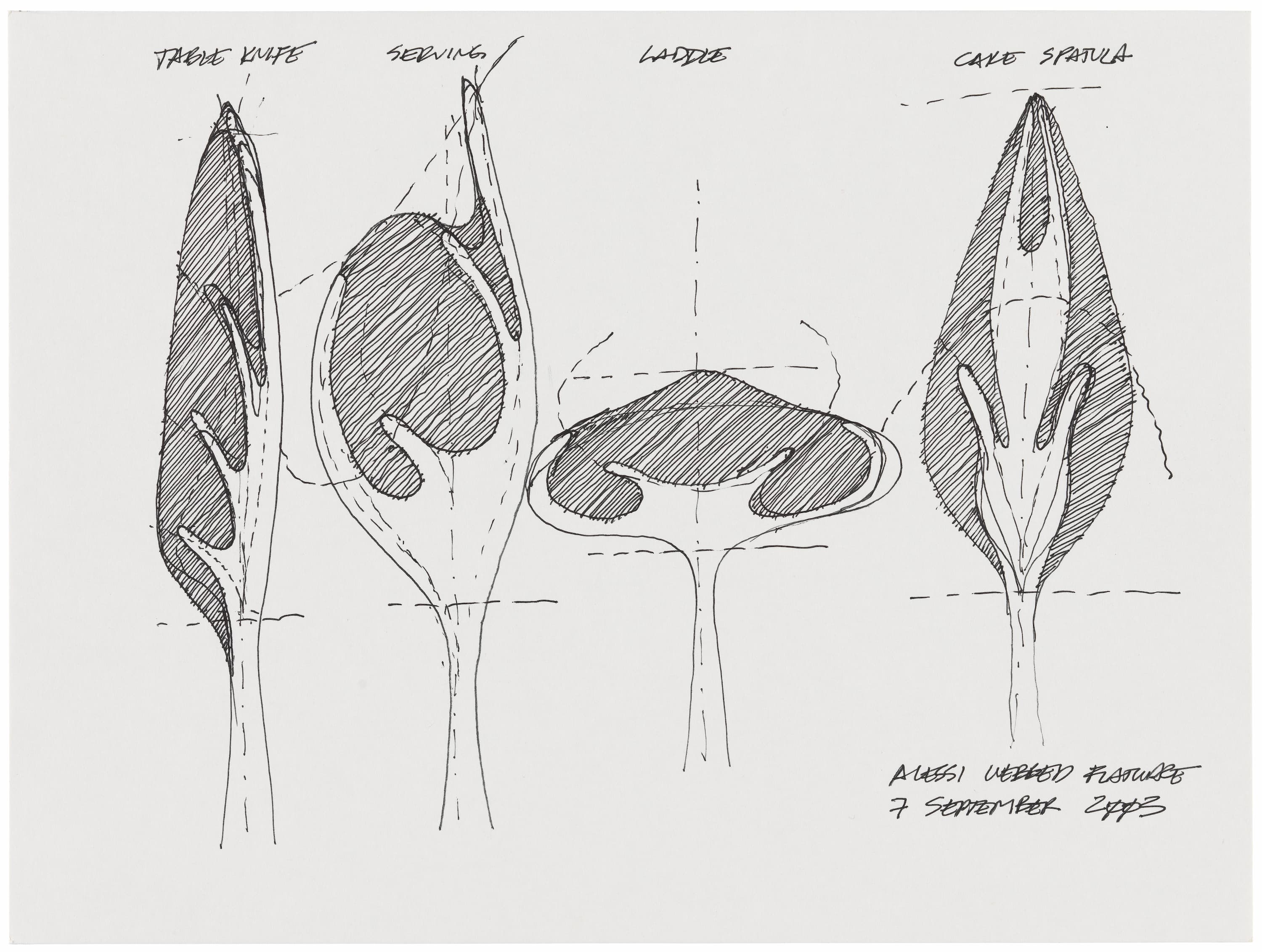

In his 1999 book Animate Form, architect and designer Greg Lynn explains his morphogenetic methodology, which leverages computational tools and digital technologies to create dynamic, adaptive, and generative forms.10 Lynn later applied this methodology to design a set of flatware for the Italian kitchenware company Alessi (cats. 62–66). Lynn began the process by designing a primitive, yet-to-be-specified, beginning, or “seed,” for the set: a bundle of tines as a handle with webbing, rather than starting with the spoon and altering it to create forks and knives, as Alessi typically does (cat. 67).11 This initial form served as a kind of DNA code capable of generating an infinite array of utensils. “How do we design a generic starting point which is latent with all of that information that needs to unfold, which lets us make all of the components or all of the elements in the set part of this continuous family?” Lynn wondered.12 To achieve this, Lynn employed animation software, originally developed for the animated film industry, where the primitive form was combined and recombined in numerous ways, facilitating a wide range of configurations and variations for specific functions (cat.68). Each individual utensil was articulated figuratively to reflect its specific function. At once familiar and uniquely strange, the resulting utensils are individually specialized yet collectively related as a family.

Designers Joris Laarman and Nervous System explore generative and parametric design processes. These approaches employ input parameters and constraints to advance a design toward a desired outcome, like an evolutionary process. Laarman’s Bone Armchair marked his first foray into using natural science to determine not only the formal appearance of an object but also the underlying structural logic that governs its engineering and construction (fig. 2). Laarman’s Adaptation Chair, from the Microstructures series, draws on the complex patterns of growing branches and roots to adjust its geometry (cat. 41). Laarman engineered the chair starting from the smallest structural and functional unit, or “cell,” imitating nature’s approach of creating the most efficient structures possible. The chair’s legs appear to organically rise from the ground like a tree, redistributing their mass at specific points in response to physical stress. As the legs grow into branches, they fan out into increasingly smaller branches that eventually form and support the seat and back of the chair, akin to how a tree’s branches support its leaf canopy (trees can add material where strength is needed). The final design simulates cellular structures to meet the needs of different areas of the chair. Each component of the chair is essential to the whole.

Nervous System is a generative design studio founded by Jessica Rosenkrantz and Jesse Louis-Rosenberg that creates products inspired by natural phenomena. Using advanced computer algorithms, the studio generates designs that mimic patterns found in nature. The Floraform Chandelier is an undulating flower-like surface composed of ten branching structures made of 3-D-printed nylon (cat. 80). The structure was grown by two generative algorithms created by Nervous System: Floraform and Hyphae. Floraform explores surface development through differential growth inspired by the biomechanics of growing leaves and blooming flowers. Hyphae is an iterative branching system based on how veins form in leaves. The large, yet airy, suspended light casts a dense forest of shadows, enveloping the viewer in an immersive environment of algorithmically grown plant forms.

Architect and designer Elena Manferdini’s installation Wall Flowers: Clover considers how nature’s ordering systems might be represented today, when computational tools have greatly increased our ability to identify and understand these geometries (cat. 73). The flora depicted in Wall Flowers: Clover appears to have been extracted from the natural world; however, upon closer inspection, the intricate blooms take on a synthetic appearance, blurring the boundary between the real and the hyperdigital. When visitors engage with the installation, their images are reflected back on a series of mirrored panels. The viewer, then, becomes an integral part of the imaginary landscape. Manferdini’s digital garden immerses the visitor in a sense of natural order taken to an extreme. Her interchange between reality and the digital world raises questions about the fundamental uncertainty of our digital age and its impact upon the human race.

In their pursuit to replicate natural forms like tropical plants, construct fractal-like structures, or simulate plant growth, architects, artists, and designers harness the power of natural analogs to disrupt our mechanized expectations. They poignantly remind us of the intricate relationships between our industrialized world and the natural environment. Their creative endeavors prompt us to pause, reevaluate, and explore harmonious ways to navigate the realms of human innovation and the enduring beauty of the natural world, urging us toward a more balanced and sustainable coexistence.

-

Stephen R. Kellert, Judith Heerwagen, and Martin Mador, eds., Biophilic Design: The Theory, Science and Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2011). ↩︎

-

Studies have shown that figurative and abstract natural forms evoke strong emotional and aesthetic responses in the viewers. N Barsukova, “The Process of Transformation Natural Forms into an Associative Design Model,” IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering 463, no. 2 (2018), https://doi.org/10.1088/1757-899X/463/2/022044. ↩︎

-

E. H. Gombrich, The Sense of Order: A Study in the Psychology of Decorative Art (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1979). ↩︎

-

Benoit B. Mandelbrot, The Fractal Geometry of Nature, updated edition (1977; New York: W. H. Freeman, 1982). ↩︎

-

Richard P. Taylor, Adam P. Micolich, and David Jonas, “Fractal Analysis of Pollock’s Drip Paintings,” Nature 399, no. 422 (1999), https://doi.org/10.1038/20833. ↩︎

-

Ruth Richards, “A New Aesthetic for Environmental Awareness: Chaos Theory, the Beauty of Nature, and Our Broader Humanistic Identity,” Journal of Humanistic Psychology 41, no. 2 (Spring 2001), https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167801412006. ↩︎

-

Nikos A. Salingaros, “Fractal Art and Architecture Reduce Physiological Stress,” Journal of Biourbanism 2, no. 2 (2012): 11–28. ↩︎

-

The potential for incorporating fractals into the built environment as a novel approach to reducing stress is also discussed in Richard Taylor, “Reduction of Physiological Stress Using Fractal Art and Architecture,” Leonardo 39, no. 3: 245–51, https://doi.org/10.1162/leon.2006.39.3.245; Yannick Joye, “Architectural Lessons from Environmental Psychology: The Case of Biophilic Architecture,” Review of General Psychology 11, no. 4 (2007): 305–28, https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.11.4.305. ↩︎

-

Emile F. Doungmo Goufo, “On the Fractal Dynamics for Higher Order Traveling Waves,” Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 148 (July 2021), https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chaos.2021.111059. ↩︎

-

Greg Lynn, Animate Form (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1999). The term “morphogenetic” combines the words “morphogenesis,” which refers to the biological (and geological) process that enables an organism (or landform) to take shape, and “genetic,” which pertains to the underlying patterns of generation or development. ↩︎

-

Greg Lynn, “Machine Language,” Log 10 (Summer–Fall 2007): 61. ↩︎

-

Greg Lynn, “You’ll See It When You Know It” (lecture, SCI-Arc, Los Angeles, CA, April 8, 2008), https://channel.sciarc.edu/browse/greg-lynn-you-ll-see-it-when-you-know-it-april-8-2008. ↩︎