Listen to Florence Williams read Big Nature, Big Art, and the Necessary Euphoria of Awe

In the winter of 2019, Dacher Keltner visited his dying younger brother. In his mid-50s, Rolf Keltner was losing his battle with cancer. The older brother rested his hand on Rolf’s shoulder. He sensed a light radiating from his brother, a force around his body, pulling him away. He felt immense sorrow but also the enormity of the mysteries of life and death. In the presence of his brother and these immemorial forces of time, he briefly lost his sense of being an embodied individual.1

Keltner, a psychologist at the University of California, Berkeley, later understood exactly what he’d experienced in that moment: awe. Keltner had been studying this emotion for years, usually in his lab, elicited in volunteers watching videos of things like the Earth from space. But occasionally Keltner and his colleagues would take subjects out into the real world to stand under giant trees or raft in the wilderness or look at dinosaur skeletons in a museum while filling out questionnaires or offering up saliva to test hormones.

A child of a painter and a poet growing up in the ’60s, Keltner was in some ways primed to study this emotion.2 Natural beauty was all around: Men were landing on the moon. His neighbors in Topanga Canyon included some of the decade’s most enduring musicians. Until Keltner was out of graduate school, the emotion of awe had hardly been studied by academics, even those who specialize in emotions. And yet, argued Keltner, it lay at the very heart of what it means to be human.

Closely linked to mysticism and other transcendental feelings, awe has been shown to foster cooperation, humility, reverence, caretaking, emotional well-being, and physical health.3

It may be the defining emotion of our species.

Perhaps it’s no coincidence that as so much in our world seems to be teetering on the edge of instability—environmental change, social fragmentation, technological distrust, postpandemic malaise, anxiety, and disease—awe is enjoying something of a moment. As scientific studies elevate the status of this emotion, as more clinicians recommend it to patients, as more people on their own seem to be craving analog experiences and connections to each other, to art, and to the natural world, awe is now, in some circles, touted as a plausible and necessary corrective to despair.

But what exactly is awe? And why does it sometimes precipitate dramatic mental and physical effects?

In attempting to define this somewhat ineffable emotion, Keltner and fellow psychologist Jonathan Haidt wrote a groundbreaking paper on the topic in 2003. Titled “Approaching Awe, a Moral, Spiritual, and Aesthetic Emotion,” it surveys the writings of mystics, poets, and philosophers, including Edmund Burke, who in 1757 described the sublime, in Keltner and Haidt’s words, “as the feeling of expanded thought and greatness of mind that is produced by literature, poetry, painting, and viewing landscapes.” 4

The paper goes on to explain that people often feel awe in the presence of vast natural features such as sweeping views, mountains, storms, and oceans. But the authors noted that “vastness” can refer to conceptual vastness as well, such as quantum physics or evolution or any idea that blows your mind. People can also feel awe in response to objects with infinite, or just alluring, repetition, such as fractal patterns found in forests, along coastlines, and in cloud formations. Fractal patterns, according to mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot, are patterns that repeat at different scales and express some principles of unity, symmetry, and self-similarity.5 It’s no wonder that nature facilitates states of awe.

But vastness is not the only ingredient. Awe requires something of a double take. While encountering awe, we are jolted—even momentarily—out of the ordinary. We may be a little surprised, a little confused, certainly fully absorbed. Keltner and Haidt conclude that a classic awe experience must encompass two main components: a sense of vastness and a little bit of mystery to the point that we seek to adjust our mental maps.

In his 2023 book, Awe: The New Science of Everyday Wonder and How It Can Transform Your Life, Keltner expands on this earlier definition to include a third component: a feeling that we are part of systems larger than the self. This is ultimately what makes awe a transcendent—and healing—emotion.

To figure out how often people experience awe and under what conditions, Keltner and colleagues gathered thousands of narratives from twenty-six countries. They broke the results into eight major categories of awe, or as Keltner puts it, “wonders of life”:

Moral Beauty

People around the world are most moved to awe by witnessing other people in acts of courage, love, strength, kindness, and overcoming.

Collective Effervescence

A phrase coined by French sociologist Émile Durkheim, it refers to shared experiences leading to an electric and powerful sense of “we,” including weddings, funerals, political rallies, dancing, singing, or marching together, watching an eclipse in a group, and so on.

Nature

Nature-elicited awe, such as from viewing impressive features or encountering wildlife, accounts for about a quarter of contemporary awe experiences.

Music

Hearing music, playing music, chanting, and singing can transport us, fill us with vibrations, and make us feel connected to something beyond ourselves through symbols and physical sensation.

Visual Design

From patterns to colors to hallucinations to architectural grandeur, visual design can open, in Aldous Huxley’s famous phrase, the “doors of perception.”

Spirituality and Religion

Whether through dramatic conversions and visitation or simple meditative practice, the very definition of spiritual means connecting with forces larger than the self.

Life and Death

Few things move us as profoundly as witnessing these fundamental and universal passages.

Epiphany

A classic feature of conceptual awe, this is the moment we achieve insight or view an idea in a wholly new way.6

For those of us who love museums, it’s no wonder that visual design and other sensory encounters can lead to feelings of being transported outside the self. Museums can offer several types of awe at once: Visual exhibits may incorporate music or images of nature. Being surrounded by others creates a collective experience. Perhaps we achieve new insight from seeing emotions or ideas represented artistically. And large sculptures and earthworks offer opportunities to encounter the vastness of scale, not to mention the technical and creative wonders of human ingenuity.

Consider the installation Clay Houses by Andy Goldsworthy at the Glenstone Museum outside of Washington, DC.

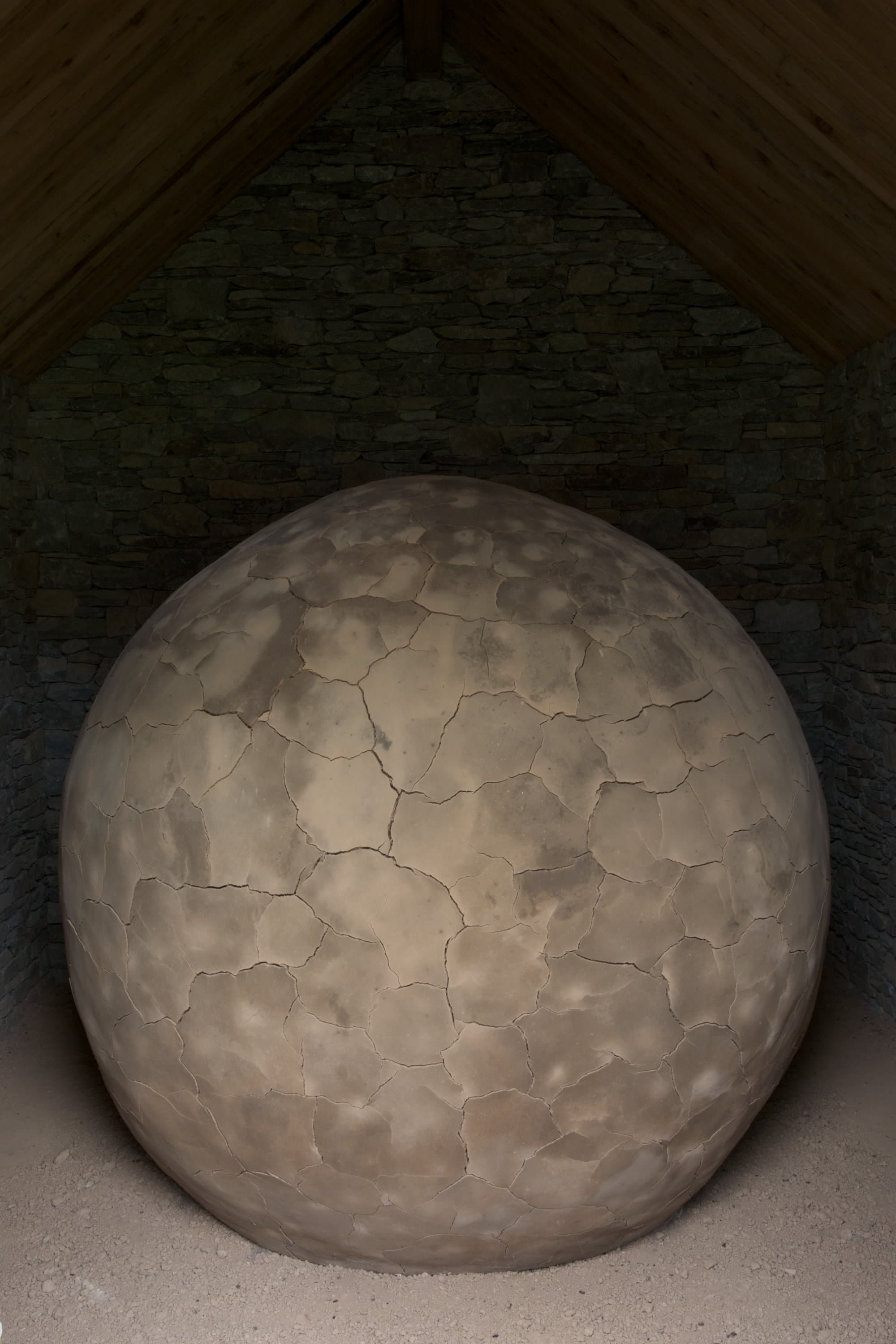

The small stone cabins arise without fanfare alongside a wooded trail. Handcrafted from small stones, they look like something you might stumble upon on a desolate Scottish moor (fig. 1). From the outside, they appear the same: approximately thirteen feet high, sixteen feet wide, and nineteen feet long, topped by a simple pointed slate roof. You walk in through the first cabin’s wooden door, and it takes your eyes a moment to adjust to the dark interior. You might let out a small squeal of delight or surprise as your eyes settle on a large perfectly round earthen orb in the middle of the otherwise empty room (fig. 2). The orb is much larger than the doorway, substantially taller than a person, cracked and slightly desiccated. How did it get here? Why doesn’t it crumble? Further investigation reveals that it’s made of brown clay from the site mixed with horsehair, human hair, and sheep’s wool. People around you take selfies in front of the orb as if they have just emerged from a giant dirt bubble. You smile at each other. The room is called simply Boulder.

“What could possibly be in the next hut?” you wonder. This is the artist’s intention. In his statement for the museum, Goldsworthy wrote, “I don’t want to give anything away. Finding the work inside is part of the sculpture’s nature. If you let it be known they are art, it takes away from the art.”7

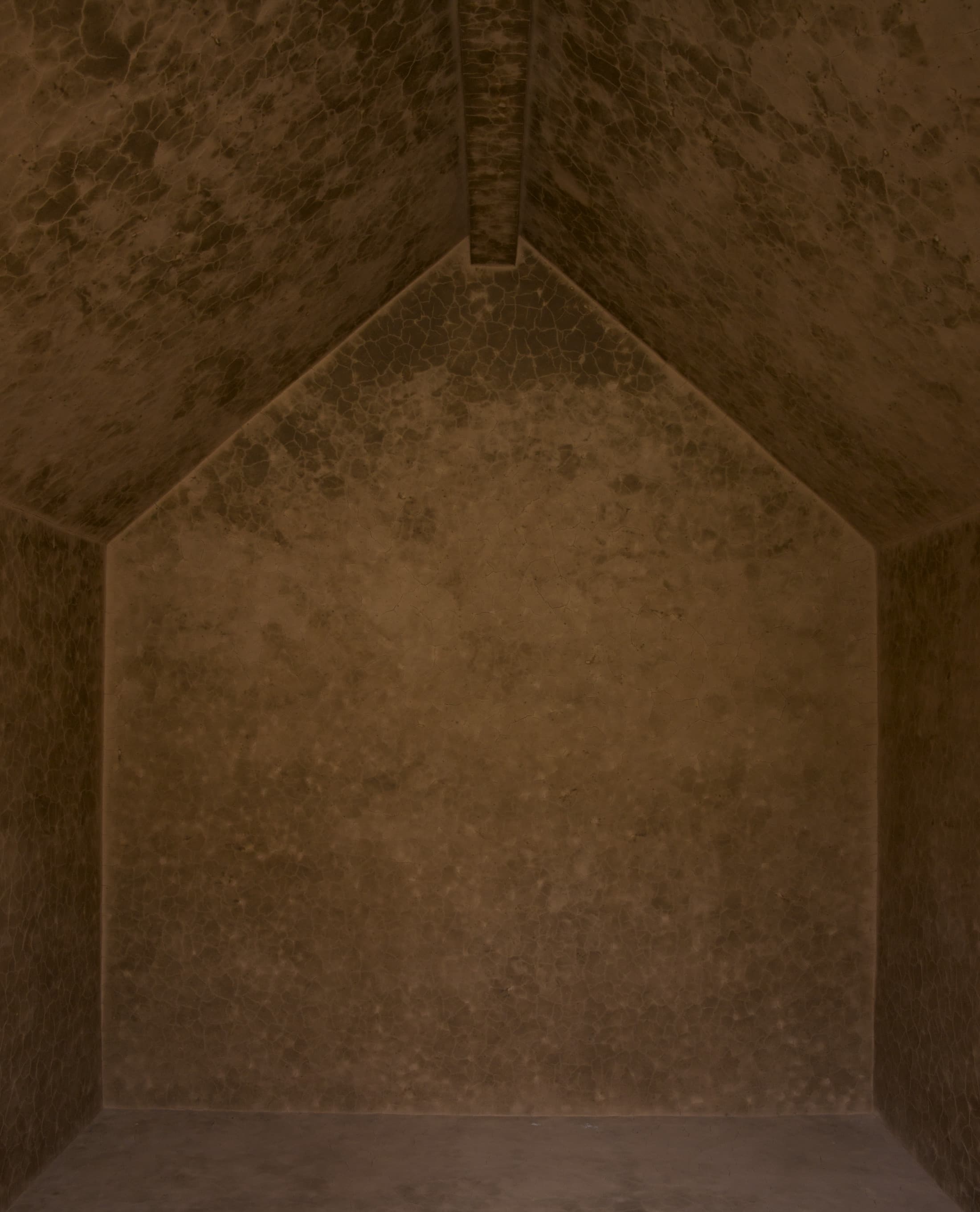

And so you amble over to that entrance. Only a few people are allowed in at one time. You step over the threshold. This room contains no object. Titled Room, it is simply plastered with the earthen material on every wall, ceiling, and floor surface, giving the space an ancient, cave-like quality (fig. 3). It absorbs sound and light. Is it a house? A mud-covered church? A gremlin’s secret lair? If it rains, will it wash away? A stone exterior, a mud interior. It is unlike anything you have ever seen. You stop to take it in, to consider. In the stopping and sensing, there is a feeling of alertness, and then peace. Time slows down.

And finally: the third stone cottage. This one also contains no object, but it holds another surprise. The small room’s back wall recedes in a series of concentric circles that telescope away from the viewer into a false rear wall (fig. 4). The symmetry is perfect, but organic. Circles inside a Euclidean room. The pleasing shapes are universal, mysterious, and safe at the same time. This could be the site of a primeval ritual, harkening back to a womb or a giant owl’s eye or a cosmic wormhole. The room is titled Holes.

You step out into the forest. You feel lighter. Amused. Curious. Tender.

But did you experience awe?

Let’s break it down.

Did you experience a sense of surprise and the feeling that this is something out of the ordinary? Decidedly so. What about a sense of mystery? Probably so. Many questions likely arose about both the artistic intention and the technical fabrication. The rooms are made from mud, and yet while much of Goldsworthy’s work is ephemeral, Clay Houses is deceptively sturdy. On a deeper level, you may very well have sensed the mystery behind the human desire to affiliate with biophilic materials and the universal shapes represented. What about vastness? In these rooms, you may have marveled at the time required to hand build the stone structures and the installations within. You may have even subconsciously connected to a deeply evolved sense of human pleasure in these shapes and materials, something that ties you by an invisible thread to your ancient ancestors and to all people. The installation speaks to time, to space, to collective memory. In the presence of this art, perhaps you felt your individual self to be slightly less significant.

In case you’re wondering if similar experiences have led you to a classic encounter with awe, researchers from the University of Pennsylvania along with Italian colleagues developed an “Awe Experience Scale” that encompasses six domains.8 In it, viewers rate their responses to such statements as “I noticed time slowing,” “I felt my sense of self was diminished,” “I had the sense of being connected to everything,” “I experienced something greater than myself,” “I had goosebumps, or felt my jaw drop,” and “I felt challenged to mentally process what I was experiencing.” You can add up your scores and see how you fared.

It’s important to acknowledge, though, that not everyone experiences awe in the same way. As individuals, we have different capacities for awe, just as we have different dispositions to feel optimism or fear.9 Some of us are more jaded, less playful, less open to mysteries, and less prone to having goosebumps or a tingly feeling when encountering aesthetic stimuli. According to research in the emerging field of neuroaesthetics, about half of the population generates goosebumps in response to art and poetry (nature, music, and other stimuli aren’t typically measured).10 The personality trait most closely associated with this tendency is openness, characterized by curiosity, exploration, and comfort with novel experiences.11

Several years ago, University of Utah psychologist Paula Williams and colleagues made an interesting discovery. They already knew that “aesthetic sensitivity,” i.e., the capacity to be moved by beauty, is associated with prosocial engagement, pro-environmental attitudes, and a sense of connection to the living world. Using brain-imaging data from the Human Connectome Project, Williams’s lab discovered that people who responded positively to the goosebumps question also show greater resting-state connectivity in the white matter in their brains. They show strong neural connections between the sensory-motor parts of their brains and the parts that make up the default mode network, sometimes considered the seat of the self.12 The goosebump people are also the ones who report being the most resilient after stressful life events.13

Williams was interested to know why. What was the relationship between being awe prone and being resilient? The brain connectivity itself could be part of the answer. People who are moved by art appear to have an ability to take the sensory stimulation—the chords of a sad song, the vastness of the Milky Way, the pleasure of biophilia—and reflect on their own lives and journeys. When we feel connected to our ancestors or to living plants and animals, we feel less lonely. We gain perspective on our problems. We feel the universality of our plight.

Experiencing awe through art amplifies our narrative tendencies, enabling us to connect with the stories being told. We become active participants, cocreating meaning and finding personal resonance. We may find metaphors in the art or build on the artist’s creation to tell ourselves stories about our values, our own growth, or our place in a larger world.

The meaning-making theory sounds grand, but Williams has another, more physiologically grounded explanation tied to the slight discomfort we feel when we encounter a novel mystery. The goosebumps themselves—similar to the raised hackles on a dog’s back when facing danger—may be a mini version of a threat response. When we experience something we don’t understand, our nervous system pays close attention. Is this safe? What is happening here? Think of sitting near the horn section during a performance of Beethoven’s Symphony no. 5 in C Minor. The second phrase of the first movement ends with a climactic horn solo in which the sound wave vibrations enter the listener’s body in a dramatic, unfamiliar, even unnerving way. And yet, soon, the listener is wholly caught up in the emotional height of the music followed by the resolution of tension. It’s not an easy or mild experience. As the late neurologist Oliver Sacks put it, “Music can pierce the heart directly.”14

Awe thrives in the face of mystery and the unknown. Experiencing aesthetic awe in this way may be a sort of practice for the stresses of life, argues Williams. “The term I’ve come to use is that it’s a kind of stress inoculation,” she says. “If you do it a lot, then you are always challenging your system a bit and perhaps training yourself to have comfort with novelty and things that are challenging.”15

Of course, not all awe makes us uncomfortable, or at least not for long. Many things that are novel are also highly pleasurable. Accordingly, there are other neurological and endocrinological bases for why we feel good when we encounter awe. One study indicated that while watching videos depicting acts of moral courage, subjects produced more oxytocin, a neurotransmitter linked to emotional bonding, a sense of unity with others, and overall positive well-being.16 Encounters with awe may also release dopamine and activate reward networks in the brain.17

For a paper published in the journal Emotion in 2015, researchers in Keltner’s lab at UC Berkeley asked one hundred undergraduates to fill out questionnaires assessing their levels of different positive emotions such as amusement, contentment, joy, pride, love, compassion, and awe.18 The subjects also supplied saliva samples to measure an inflammatory cytokine called IL-6. Chronically elevated levels of this molecule are associated with stress as well as numerous illnesses including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and depression. In the study, those who recently experienced awe had healthier levels of IL-6, and awe was the only positive emotion predicting lower levels.

Neuroscience studies suggest that awe also quiets down activation in the self-referential default mode network as we either think less about our own dramas in moments of amazement or we connect our problems in a more holistic way to the external stimuli.19

Real-world studies in the field confirm awe’s tendency to diminish our egos. In one, researchers asked tourists at both Fisherman’s Wharf (a commercial destination in the city of San Francisco) and a scenic overlook at Yosemite National Park to rate their experiences of awe and draw a picture of themselves on graph paper. The Yosemite tourists experienced far more awe, and they also drew their bodies as 33 percent smaller than the urban tourists. They also wrote their signatures in smaller penmanship.20

After the spectacular solar eclipse in the summer of 2017, psychologists at the University of California, Irvine, analyzed the language of seven million Tweets.21 Tweets sent from the cone of totality used significantly more universal words like “we” and fewer individual words like “I.”

Hermann Hesse said it well, if a bit verbosely, in 1926:

Whenever I experience part of nature, whether with my eyes or another of the five senses, whenever I feel drawn in, enchanted, opening myself momentarily to its existence and epiphanies, that very moment allows me to forget the avaricious, blind world of human need, and rather than thinking of issuing orders, rather than acquiring or exploiting, fighting or organizing, all I do that moment is “wonder,” like Goethe, and not only does this wonderment establish my brotherhood with him, other poets, and sages, it also makes me a brother to those wondrous things I behold and experience as the living world: butterflies and moths, beetles, clouds, rivers and mountains, because while wandering down the path of wonder, I briefly escape the world of separation and enter the world of unity.22

Those feelings of noninvolvement, even when brief, are very good for our mental health. In lab experiments that induce awe, volunteers report a reduced awareness of day-to-day stress and feelings of being less hassled. Either because of improved moods or because of something particular to awe itself, volunteers engage in more generous behaviors, for example sharing money earned in computer games or folding more paper cranes for tsunami victims.23

As Keltner puts it, “Awe is about as good for your mind and body as anything. It reduces inflammation, so it’s good for your immune system. It activates the vagus nerve, which is good for your cardiovascular system. It’s good for your basic digestive processes. And it’s good for your mind. Even ten minutes of awe makes you feel less self-critical, less stressed, less in pain, more creative, and more of just about all the things we care about in the well-being literature.”24

It’s one thing to feel good in the moments during or right after awe. But emerging science also suggests that awe may be the primary mechanism by which people achieve long-term improvements in symptoms of PTSD, in addictive behaviors, and in feelings of fear around terminal illness.25 Nowhere are these results more apparent than around the therapeutic use of psychedelics. In an extensive series of case-controlled studies at Johns Hopkins Center for Psychedelic & Consciousness Research, where patients are administered psilocybin (a derivative of “magic mushrooms”), more than half of them report cessation of clinical symptoms a year after treatment.26 They also report enduring feelings of gratitude, life satisfaction, humility, and well-being. In the high-dose groups, most patients encounter a scientifically assessed “mystical” experience, which is very similar to high scores on the Awe Experience Scale. They see visual patterns, feel that time is suspended, believe they are receiving epiphanic truths, and experience feelings of unity together with a loss of ego. It is, essentially, awe on Miracle-Gro.

In a 2018 paper in the International Review of Psychiatry, Professor Peter Hendricks of the University of Alabama speculates that intense or “big” awe is transformative because it breaks down established patterns and narratives of self-concept. What’s left in their place are new valuations of the self and a profound sense of belonging and connection. “For those suffering from depression, end-of-life distress, or other conditions marked by rumination,” writes Hendricks, “attention diverted away from the self and toward the transcendent (e.g., family, community, the external universe, a belief system) is likely experienced as liberating if not sublime.”27

As Keltner and Haidt put in their 2003 paper, “Awe-inducing events may be one of the fastest and most powerful methods of personal change and growth.”28

Awe researcher Michelle Shiota at Arizona State University agrees, believing that awe opens a rare window of opportunity to change our belief systems about the world and about ourselves. In those moments of amazement, we can reconsider everything we thought we knew. We can form new allegiances and beliefs. But this isn’t always a good thing, she points out. Cult leaders, religious figureheads, celebrities, and politicians utilize the trappings of vastness and physical and moral beauty to gain or indoctrinate new followers.

As Shiota wrote in a 2021 paper, “Awe seems to produce a little earthquake in the mind, a moment of cognitive malleability offering a chance to expand and reconstruct one’s mental model of the world. The model that emerges depends on what happens in the moments during and after encountering the awe stimulus. We still know far too little about that phase of awe.”29

Nevertheless, she recommends we go out of our way to experience awe, on our terms, often. “Keep your eyes open; notice the unexpected,” she suggests. “Seek out new music, literature, visual art, dance, or drama, and learn to appreciate these art forms more deeply . . . the goal is to deepen your understanding of the art form so that you recognize the revolution, the extraordinary achievement, when you encounter it.”30

If big awe can be transformative, what about small awe, the kind we are more likely to run into on a regular basis?

Many psychologists say yes. While grieving his brother, Keltner sought out narratives of moral beauty, reading biographies of Gandhi. He made an effort to regularly lose himself in music, listening at home and occasionally attending symphonies. Hofstra University PhD student and awe researcher Marianna Graziosi sought relief over the death of a loved one by watching her toddler niece play in the gentle surf of the ocean.31 Michael Amster, a medical doctor and the coauthor of 2023’s The Power of Awe, writes of resolving his depression through finding small moments of natural beauty throughout the day. He calls this practice “micro-dosing awe.” He now prescribes daily awe to his patients suffering from mood disorders and chronic pain.32

In fact, says Amster, beauty is all around us. But we need to pay attention and look for it. As Walt Whitman, the patron saint of awe-seekers, wrote, “A leaf of grass is no less than the journey-work of the stars.”33

When we practice tuning into daily moments of beauty, we can learn to get better at cultivating awe. At the same time, we’ll be cultivating a more resilient mindset grounded in curiosity, cognitive flexibility, mindfulness, and creativity, says Utah’s Paula Williams.34

Once upon a time, it was easy to find awe. Our ancestors looked up at the sky every night. They sat around a fire and told stories of courage. They danced and sang together. They regularly encountered wild animals. They searched for and cherished fresh water and living plants. They worshipped and contemplated cycles of nature. Our capacity to experience awe no doubt helped our species survive, as it allowed individuals to recover from stress. Moreover, it helped bond us to each other to forge the cooperation necessary for our evolution.

If experiencing the sacred and the awesome are so good for us, and so good for our social fabric, what does it mean that we are living in a manner so disconnected from nature, and increasingly, from face-to-face interactions?

It means this: the burden now falls upon art and culture to help replace the daily awe we used to receive from the natural world and from each other. While the Milky Way is now less accessible, art has in some ways become more accessible than ever before. Online platforms and virtual exhibitions allow individuals from diverse backgrounds to encounter awe-inspiring creations regardless of their geographical location. The intersection of art and science has given rise to awe-inspiring installations that merge aesthetics, technology, and scientific principles. Viewers can experience full-sensory immersive wonders that offer windows into the mysteries of the universe and the complexity of ecological and human systems.

As a society, though, we need to keep improving access to the arts. Opportunities to experience awe should be more equitably distributed across race and class. To be our best human civilization, we should be expanding arts education not shrinking it. We should be teaching children how the natural world works and allowing them to spend more time in outdoor classrooms.

Encountering awe is central to the emotional and creative core of being human.

As Goethe once wrote, “I am here, that I may wonder.”35 Mary Oliver agreed, writing, “Let me / keep my mind on what matters, / . . . which is mostly standing still and learning to be / astonished.”36

-

This story is recounted in Dacher Keltner, Awe: The New Science of Everyday Wonder and How It Can Transform Your Life (New York: Penguin Press, 2023), xx–xxiv. ↩︎

-

Dacher Keltner, personal communication with the author, April 2023. ↩︎

-

Keltner, Awe, 36, 39–41. ↩︎

-

Dacher Keltner and Jonathan Haidt, “Approaching Awe, a Moral, Spiritual, and Aesthetic Emotion,” Cognition and Emotion 17, no. 2 (March 2003): 300. ↩︎

-

John Horgan, “Who Discovered the Mandelbrot Set,” Scientific American, March 13, 2009, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/mandelbrot-set-1990-horgan. ↩︎

-

Keltner, Awe, 10–18. ↩︎

-

“Clay Houses: Boulder-Room-Holes (2007–2008),” Glenstone Museum, https://www.glenstone.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/QR-Code-Sheet_Goldsworthy_11-18-2021.pdf. ↩︎

-

David B. Yaden et al., “The Development of the Awe Experience Scale (AWE-S): A Multifactorial Measure for A Complex Emotion,” The Journal of Positive Psychology 14, no. 4 (July 2018): 474–88. ↩︎

-

Paula G. Williams, personal communication with the author, February 2020. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Paula G. Williams et al. “Individual Differences in Aesthetic Engagement Are Reflected in Resting-State fMRI Connectivity: Implications for Stress Resilience,” NeuroImage 179 (October 2018): 156–65, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6410354/. ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Paula G. Williams, personal communication with the author, April 2023. ↩︎

-

Oliver Sacks quoted in Ana Sandoiu, “How Music Helps the Heart Find Its Beat,” MedicalNewsToday, April 17, 2018, https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/321535. ↩︎

-

Williams, personal communication with the author, April 2023. ↩︎

-

Andrew L. Thomson and Jason T. Siegel, “Elevation: A Review of Scholarship on a Moral and Other-Praising Emotion,” The Journal of Positive Psychology 12, no. 6 (2017): 628–38. ↩︎

-

Jake Eagle and Michael Amster, The Power of Awe (New York: Hachette Go, 2023), 79–80. ↩︎

-

Jennifer E. Stellar et al., “Positive Affect and Markers of Inflammation: Discrete Positive Emotions Predict Lower Levels of Inflammatory Cytokines,” Emotion 15, no. 2 (April 2015). ↩︎

-

Maria Monroy and Dacher Keltner, “Awe as a Pathway to Mental and Physical Health,” Perspectives on Psychological Science 18, no. 2 (2023): 309–20, doi: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10018061/. ↩︎

-

Y. Bai et al., “Awe, the Diminished Self, and Collective Engagement: Universals and Cultural Variations in the Small Self,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 113, no. 2 (August 2017): 185–209. ↩︎

-

Sean P. Goldy, Nickolas M. Jones, and Paul K. Piff, “The Social Effects of an Awesome Solar Eclipse,” Psychological Science 33, no. 9 (2022): 1452–62, https://doi.org/10.1177/09567976221085501. ↩︎

-

Hermann Hesse, quoted in Maria Popova, “How to Be More Alive: Hermann Hesse on Wonder and the Proper Aim of Education,” The Marginalian, accessed August 15, 2023, https://www.themarginalian.org/2023/07/06/hermann-hesse-wonder-butterflies/. ↩︎

-

Monroy and Keltner, “Awe as a Pathway to Mental and Physical Health.” ↩︎

-

Keltner, personal communication with the author, April 2023. ↩︎

-

Tingying Chi and Jessica A. Gold, “A Review of Emerging Therapeutic Potential of Psychedelic Drugs in the Treatment of Psychiatric Illnesses,” Journal of the Neurological Sciences 411 (April 2020), article 116715. ↩︎

-

Albert Perez Garcia-Romeu, Assistant Professor, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, personal communication with the author, April 2023. ↩︎

-

Peter S. Hendricks, “Awe: A Putative Mechanism Underlying the Effects of Classic Psychedelic-Assisted Psychotherapy,” International Review of Psychiatry 30, no. 4 (2018): 337. ↩︎

-

Keltner and Haidt, “Approaching Awe,” 312. ↩︎

-

Michelle N. Shiota, “Awe, Wonder, and the Human Mind,” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1501 (October 2021): 87. ↩︎

-

Ibid., 88. ↩︎

-

Marianna Graziosi, PhD candidate, Hofstra University, personal communication with the author, April 2023. ↩︎

-

Eagle and Amster, The Power of Awe, 29. ↩︎

-

Walt Whitman, “Song of Myself,” section 31 (1892), Poetry Foundation, accessed August 15, 2023, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45477/song-of-myself-1892-version. ↩︎

-

Paula G. Williams, personal communication with author, February 2020. ↩︎

-

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, quoted in Popova, “How to Be More Alive.” ↩︎

-

Mary Oliver, “Messenger,” in Thirst (Boston: Beacon Press, 2006), 1. ↩︎